The funnel plot is a beloved meta-analysis tool. It is typically used to answer the question of whether a set of studies exhibits publication bias. That’s a bad question because we always know the answer: it is “obviously yes.” Some researchers publish some null findings, but nobody publishes them all. It is also a bad question because the answer is inconsequential (see Colada[55]). But the focus of this post is that the funnel plot gives an invalid answer to that question. The funnel plot is a valid tool only if all researchers set sample size randomly [1].

What is the funnel plot?

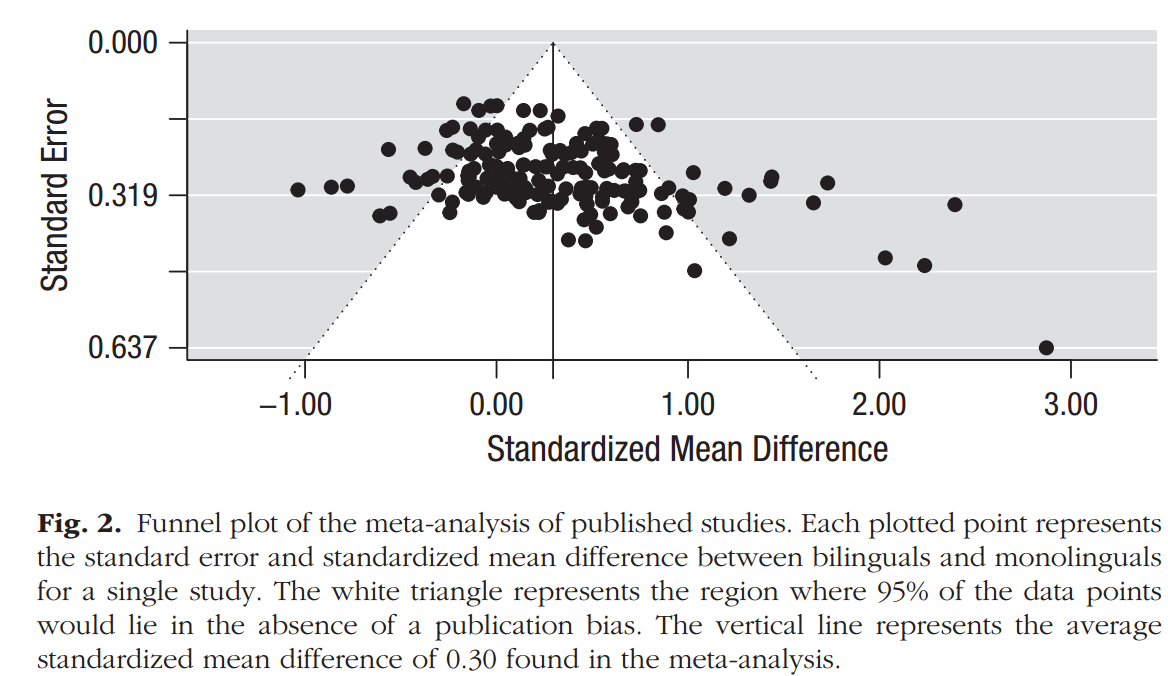

The funnel plot is a scatter-plot with individual studies as dots. A study's effect size is represented on the x-axis, and its precision is represented on the y-axis. For example, the plot below, from a 2014 Psych Science paper (.htm), shows a subset of studies on the cognitive advantage of bilingualism.

The key question people ask when staring at funnel plots is: Is this thing symmetric?

The key question people ask when staring at funnel plots is: Is this thing symmetric?

If we observed all studies (i.e., if there was no publication bias), then we would expect the plot to be symmetric because studies with noisier estimates (those lower on the y-axis) should spread symmetrically on either side of the more precise estimates above them. Publication bias kills the symmetry because researchers who preferentially publish significant results will be more likely to drop the imprecisely estimated effects that are close to zero (because they are p > .05), but not those far from zero (because they are p < .05). Thus, the dots in the bottom left (but not in the bottom right) will be missing.

The authors of this 2014 Psych Science paper concluded that publication bias is present in this literature in part based of how asymmetric the above funnel plot is (and in part on their analysis of publication outcomes of conference abstracts).

The assumption

The problem is that the predicted symmetry hinges on an assumption about how sample size is set: that there is no relationship between the effect size being studied, d, and the sample size used to study it, n. Thus, it hinges on the assumption that r(n, d) = 0.

The assumption is false if researchers use larger samples to investigate effects that are harder to detect, for example, if they increase sample size when they switch from measuring an easier-to-influence attitude to a more difficult-to-influence behavior. It is also false if researchers simply adjust sample size of future studies based on how compelling the results were in past studies. If this happens, then r(n,d)<0 [2].

Returning to the bilingualism example, that funnel plot we saw above includes quite different studies; some studied how well young adults play Simon, others at what age people got Alzheimer’s. The funnel plot above is diagnostic of publication bias only if the sample sizes researchers use to study these disparate outcomes are in no way correlated with effect size. If more difficult-to-detect effects lead to bigger samples, the funnel plot is no longer diagnostic [3].

A calibration

To get a quantitative sense of how serious the problem can be, I run some simulations (R Code).

I generated 100 studies, each with a true effect size drawn from d~N(.6,.15). Researchers don’t know the true effect size, but they guess it; I assume their guesses correlate .6 with the truth, so r(d,dguess)=.6. Using dguess they set n for 80% power. No publication bias, all studies are reported [4].

The result: a massively asymmetric funnel plot.

That's just one simulated meta-analysis; here is an image with 100 of them: (.png).

That funnel plot asymmetry above does not tell us “There is publication bias.”

That funnel plot asymmetry above tells us “These researchers are putting some thought into their sample sizes.”

Wait, what about trim and fill?

If you know your meta-analysis tools, you know the most famous tool to correct for publication bias is trim-and-fill, a technique that is entirely dependent on the funnel plot. In particular, it deletes real studies (trims) and adds fabricated ones (fills), to force the funnel plot to be symmetric. Predictably, it gets it wrong. For the simulations above, where mean(d)=.6, trim-and-fill incorrectly “corrects” the point estimate downward by over 20%, to d̂=.46, because it forces symmetry onto a literature that should not have it (see R Code) [5].

Bottom line.

Stop using funnel plots to diagnose publication bias.

And stop using trim-and-fill and other procedures that rely on funnel plots to correct for publication bias.

![]()

Authors feedback.

Our policy is to share early drafts of our post with authors whose work we discuss. This post is not about the bilingual meta-analysis paper, but it did rely on it, so I contacted the first author, Angela De Bruin. She suggested some valuable clarifications regarding her work that I attempted to incorporate (she also indicated to be interested in running p-curve analysis on follow-up work she is pursuing).

- By "randomly" I mean orthogonally to true effect size, so that the expected correlation between sample and effect size being zero: r(n,d)=0. [↩]

- The problem that asymmetric funnel plots may arise from r(d,n)<0 is mentioned in some methods papers (see e.g., Lau et al. .htm), but is usually ignored by funnel plot users. Perhaps in part because the problem is described as a theoretical possibility, a caveat; but it is is a virtual certainty, a deal-breaker. It also doesn't help that so many sources that explain funnel plots don't disclose this problem, e.g., the Cochrane handbook for meta-analysis .htm. [↩]

- Causality can also go the other way: Given the restriction of a smaller sample, researchers may measure more obviously impacted variables. [↩]

- To give you a sense of what assuming r(d,dguess)=.6 implies for researchers ability to figure out the sample size they need; for the simulations described here, researchers would set sample size that's on average off by 38%, for example, the researcher needs n=100, but she runs n=138, or runs n=62, so not super accurate R Code. [↩]

- This post was modified on April 7th, and October 2nd, 2017; you can see an archived copy of the original version here [↩]