This post is the second in a series (see its introduction: htm) arguing that meta-analytic means are often meaningless, because (1) they include results from invalid tests of the research question of interest to the meta-analyst, and (2) they average across fundamentally incommensurable results. In this post we focus primarily on problem (2), though problem (1) makes one or two guest appearances.

We did not choose this meta-analysis because it is atypical or especially problematic. We chose it because we believe it is typical and representatively problematic. Indeed, our critique is aimed at the enterprise of meta-analysis rather than at these particular meta-analysts, who, as far as we can tell, were simply doing what meta-analysts are instructed to do.

Authors of a recent PNAS article meta-analyzed 447 effects of “nudging” on behavior (.htm). In the abstract, the authors report “that choice architecture interventions [i.e., nudges] overall promote behavior change with a small to medium effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.43”, and that “the effectiveness of choice architecture interventions varies significantly as a function of technique and domain”.

This paper has gotten a fair bit of attention, both because of its claims about the average effects of nudges, and because letters published in PNAS, responding to this article, have proposed that the overall average effect may be much smaller – perhaps as low as zero – when correcting for publication bias (letter 1 | letter 2). Indeed, letter 1 is titled, “No evidence for nudging after adjusting for publication bias.”

In this post, we walk through a few studies included in this meta-analysis, and in so doing illustrate the problems with meta-analytic averages. We argue that these problems render meaningless both the published averages as well as the (ostensibly) bias-corrected versions of those averages.

Combining Incommensurable Results

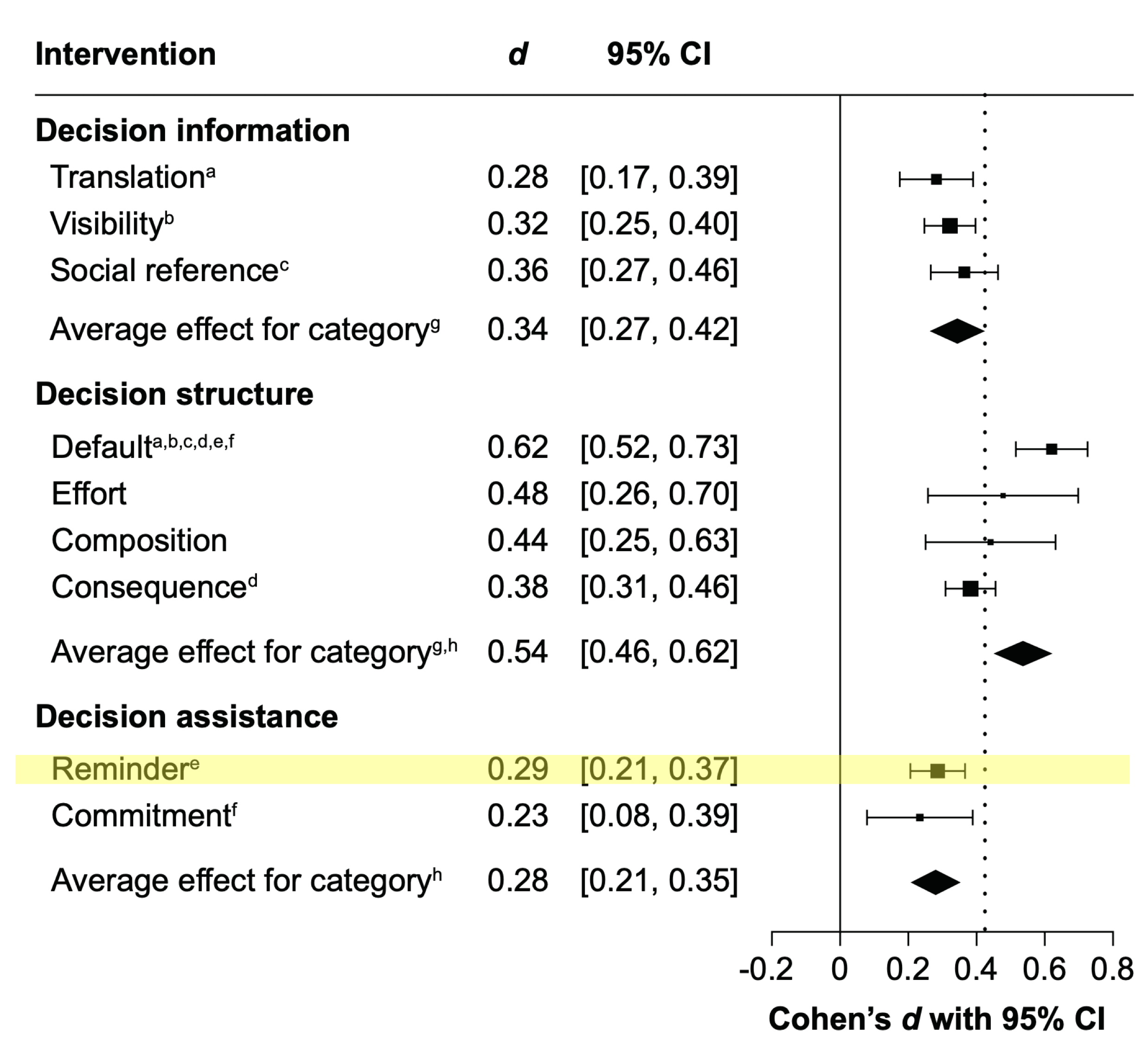

In this post, we focus our discussion on the fact that this meta-analysis averages across incommensurable results. That doesn’t mean that the authors ignored differences across studies. On the contrary, they conducted two separate moderator analyses, one that breaks down the results by nudge type (e.g., defaults vs. reminders) and one that breaks them down by domain (e.g., finance vs. food). In this section, we review studies within two of these categories, essentially asking whether it makes sense to average within a subset of studies investigating reminders or a subset of studies investigating food decisions.

Obviously, we did not approach this task by reading all ~200 studies. In the interest of (our) time and to maximize informativeness, we decided in advance to focus on the extremes: the biggest and smallest effect size estimates within each category. Do these studies provide valid answers to the question of interest to the meta-analyst? Does it make sense to combine them? Let’s take a look.

Reminders

The meta-analysts defined a reminder as anything that increases "the attentional salience of desirable behavior to overcome inattention due to information overload” [1]. Figure 4 from the PNAS paper, reprinted below, shows that the average effect of reminders is d = .29. Let’s review the studies generating the smallest and largest effect sizes and consider whether it makes sense to average across them.

1. The Smallest Reminder Effect: Something Is The “Dish of The Day” in the State of Denmark

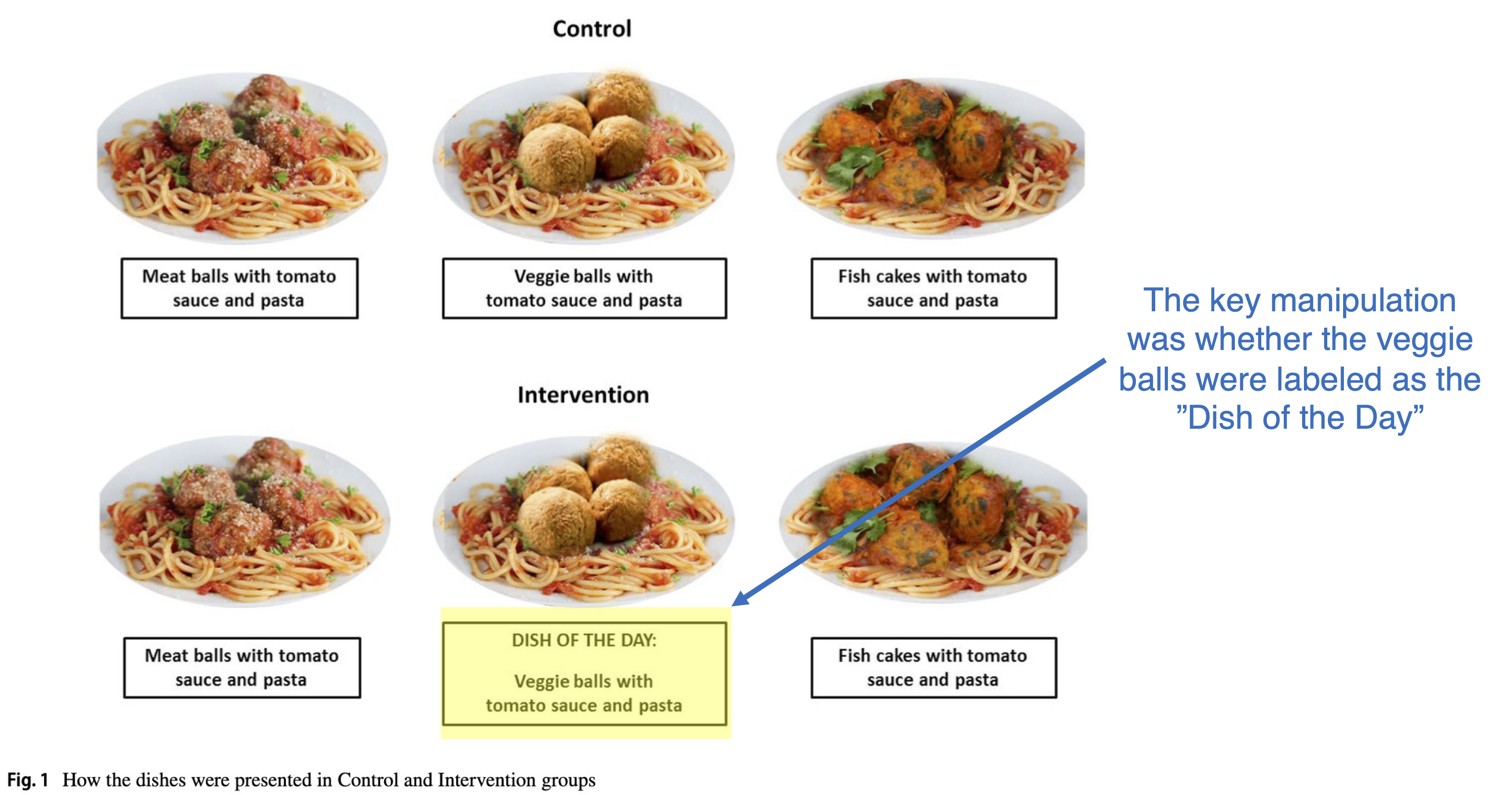

In a study published in 2020 in the European Journal of Nutrition (.htm), researchers reported a quasi-experiment conducted in four countries: Denmark, France, Italy, and the UK . Student groups were assigned, but not randomly assigned, to one of two foodservice conditions [2]. As shown in Figure 1 of the original article, the key intervention was whether the vegetarian option was labeled as the “dish of the day” or not:

The key measure was whether students chose the vegetarian option.

The original authors reported the results from each country separately, and thus so did the meta-analysts. This most negative effect of reminders in the meta-analysis (d = -.1223) represents the result that emerged in Denmark (N = 84), when only 4 out of 37 (10.8%) students in the intervention condition chose the vegetarian option vs. 7 out of 47 (14.9%) in the control condition [3], [4].

Note that it is not clear that this study should be included in the meta-analysis, since, as emphasized in the original article, students were not randomly assigned to condition, rendering these results correlational.

2. The Largest Reminder Effect: Reminding (Whites) To Go To Sleep

A study published in 2017 in Sleep Health (.htm) randomly assigned high school adolescents (N = 46) to either receive twice-daily text reminders to go to sleep on time (e.g., “Bedtime goals for tonight: Dim light at 9:30pm. Try getting into bed at 10:30pm.”) or to receive no reminders about sleep.

All participants wore a sleep monitor to measure sleep duration.

In the overall analysis, the authors found no effect of the text message reminders on sleep duration (p = .471). But then they found a significant interaction with race/ethnicity: reminders significantly increased the sleep hours of the 20 (non-Hispanic) Whites in the sample (d = 1.18, p = .028), and had no significant effect on other ethnic groups (p = .094, opposite direction).

The meta-analysis includes only the p < .05 result for (non-Hispanic) Whites, not the p > .05 result for the whole sample, and not the p > .05 result for minority students. In so doing, the meta-analysis introduced a form of publication bias – selectively including only the analyses that were statistically significant – that was not present in the original study [5].

At this point, you may want to pause to consider some questions. Do you think these studies represent valid tests of the effects of reminders? Do you think it makes sense to average these studies together? What would that average tell you?

Food Choices

In this section, we look at studies investigating nudges of food choices, because the abstract identified those as having the biggest effect (an average of d = .65). Specifically, the abstract reports that “Food choices are particularly responsive to choice architecture interventions, with effect sizes up to 2.5 times larger than those in other behavioral domains.” But does it make sense to average across studies investigating food nudges?

The Smallest Food Choice Effect: Location, Location, Location (of the Risotto Primavera)

Although the authors report that nudges targeting food choices are the most effective, some of the food nudges in the meta-analysis did not work. Indeed, the least successful food nudge involves a moderately negative effect, indicating that the nudge backfired to the tune of d = -.24. In other words, the manipulation caused a nontrivial effect in the wrong direction. Let’s try to understand what happened.

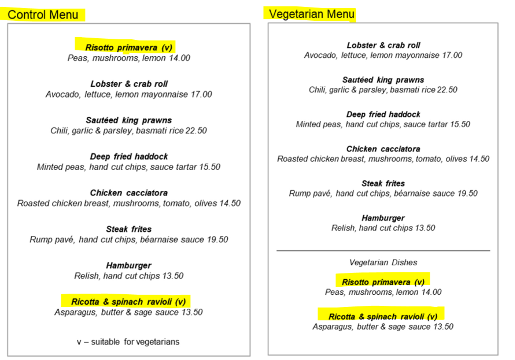

This study came from an article published in 2018 in the journal Appetite (.htm). In that study, 750 participants on Prolific were asked to “imagine they were catching up with a friend in a nice restaurant during the week” (p. 193), and to select from a menu that contained 2 vegetarian and 6 non-vegetarian dinner options. The dependent variable was whether they selected a vegetarian option.

The researchers randomly assigned participants to one of four variations of the menu. There was a “Control Menu” and three modified menus. The negative effect at issue here involved a comparison between the “Control Menu” and a “Vegetarian Menu”, for which “the vegetarian options are placed in a separate section of the menu” (p. 192). Let’s look at those two menus (the yellow highlighting is ours):

The Appetite authors included this manipulation because they noticed that some restaurants group all vegetarian options together, and the authors reportedly had the intuition that this may decrease demand for vegetarian options [6]. Since what they observed was what they expected, it is not obvious that the effect here should be negative (d = -.24) rather than positive (d = +.24)… [7].

(As a separate issue, there is a confound in the design here. See footnote: [8].)

Regardless, what this study finds is that altering the menu in this particular way produced a small(ish) (positive or negative) effect on food choices.

The Largest Food Choice Effect: Eating More When There Is More To Eat

The biggest positive effect of a nudge on food choices comes from a 2004 paper published in Obesity Research (.htm). This study, which was conducted at “a public cafeteria-style restaurant on a university campus”, asked the question: Do people eat more food when they are given more food?

As the authors report, “On 10 days over 5 months, we covertly recorded the food intake of customers who purchased a baked pasta entrée from a serving line at lunch. On 5 of the days, the portion size of the entrée was the standard (100%) portion, and on 5 different days, the size was increased to 150% of the standard portion.” The customers and those who worked in the cafeteria did not know the portions were varied, and the price was the same regardless of portion size. The finding was, um, not subtle: People ate more calories of pasta when they were given more pasta, d = 3.08.

Imagine that these were the only two food choice studies in the meta-analysis. Do you think it makes sense to average across them, and to conclude that the average effect of nudges on food choices is d = (3.08-.24)/2 = 1.42?

Conclusion #1: Meaningless Means

Imagine someone tells you that they are planning to implement a reminder or a food-domain nudge, and then asks you to forecast how effective it would be, would you just say d = .29 or d = .65 and walk away? Of course not. What you’d do is to start asking questions. Things like, “What kind of nudge are you going to use?” and “What is the behavior you are trying to nudge?” and “What is the context?” Basically, you’d say, “Tell me exactly what you are planning to do.” And based on your knowledge of the literature, as well as logic and experience, you’d say something like, “Well, the best studies investigating the effects of text message reminders show a positive but small effect” or “Giving people a lot less to eat is likely to get them to eat a lot less, at least in the near term.”

What you wouldn’t do is consult an average of a bunch of different effects involving a bunch of different manipulations and a bunch of different measures and a bunch of a different contexts. And why not? Because that average is meaningless.

Conclusion #2: What Is “The” Effect of Nudges?

What are the implications for the debate about the effect size of nudges?

In the commentary claiming, in its title, that there is “no evidence” for the effectiveness for nudges, the authors do acknowledge that “some nudges might be effective”, but mostly they emphasize that after correcting for publication bias the average effect of nudging on behavior is indistinguishable from zero. Really? Surely, many of the things we call “nudges” have large effects on behavior. Giving people more to eat can exert a gigantic influence on how much they eat, just as interventions that make it easier to perform a behavior often make people much more likely to engage in that behavior. For example, people are much more likely to be organ donors when they are defaulted into becoming organ donors [9]. For the average effect to be zero, you’d either need to dispute the reality of these effects, or you’d need to observe nudges that backfire in a way that offsets that effects. This doesn’t seem plausible to us.

The commentary authors also claim that nudges occurring within the finance domain have an effect size of zero and that there is no heterogeneity within this domain. Think about what this means. It means that any nudge that tries to influence financial decisions must have an effect size of zero. So a nudge that defaults people into a particular kind of auto insurance (J Risk Unc. 1993; .htm) has the same true effect of zero(!) as a nudge that reminds people that they wrote an honor code to pay off a loan that they were already defaulted into re-paying (JEBO 2017, .htm). Again, this doesn’t seem plausible. Much more plausible is that those publication bias corrections don’t work (see DataColada [30],[58],[59]) and that some nudges work more than others [10].

It is also worth thinking about publication bias in this domain. Yes, you will get traditional publication bias, where researchers fail to report analyses and studies that find no effect of (usually subtle) nudges. But you could imagine also getting an opposite form of publication bias, where researchers only study or publish nudges that have surprising effects, because the effects of large nudges are too obvious. For example, many researchers may not run studies investigating the effects of defaults on behavior, because those effects are already known.

In sum, we believe that many nudges undoubtedly exert real and meaningful effects on behavior. But you won’t learn that – or which ones – by computing a bunch of averages, or adjusting those averages for publication bias. Instead, you have to read the studies and do some thinking.

Coda

In this post, we reviewed only four effects from a meta-analysis of 447, but you just need four to see the problems [11]. In some cases, the studies are not valid tests of the research question. Moreover, regardless of their validity, averaging across them generates a number that has no discernible meaning.

![]()

Author feedback:

Our policy (.htm) is to share drafts of blog posts with authors whose work we discuss, in order to solicit suggestions for things we should change prior to posting, and to invite them to write a response that we link to at the end of the post. We contacted (i) the authors of the PNAS meta-analysis, (ii) those of the two PNAS letters, and of the individual studies we use as examples.

1) The authors of the meta-analysis provided valuable feedback that helped us improve the accuracy of this post.

2) Szászi et al., authors of the commentary entitled, “No reason to expect large and consistent effects of nudge interventions,” provided the following response: (.pdf). Andrew Gelman, another author of that commentary, wrote the following response: (.pdf).

3) Max Maier, an author of the commentary entitled, “No evidence for nudging after adjusting for publication bias,” provided a 180-word response (.pdf), as well as a link to a longer blog post they wrote in response: (.htm). We believe their response incorrectly equates a meaningless mean – what we are worried about – with the mean of a variable with high variance (what meta-analysts' tools model). To see the difference between meaningless means and heterogeneous means, imagine computing the average height of three structures in a city block. One structure is 2 stories high, another 2 meters high, and a third is 2 Taylor Swifts high. The average structure is 2 units high, SD=0. That mean is homogeneous but meaningless. In contrast, the average height of all members of Taylor Swift's family, measured in inches, is meaningful but heterogeneous.

4) Armando Perez-Cueto, author of the “Dish-of-the-day” study, provided helpful feedback on the post and helpful details about that study. Dario Krpan, author of the Vegetarian menus study, provided helpful feedback on the post. And Barbara Rolls, author of the portion size study, provided helpful feedback on the post as well as this response:

My lab does not work on nudging so I am surprised that our careful demonstration that portion size affects intake outside a lab would be included in such a meta-analysis. There was no nudging involved in the study. Covertly in the context of a cafeteria, the pasta dish was either bigger or smaller. There was no choice except to order pasta rather than something else, and there was no nudge.

Like you, I share concerns about such meta-analyses and systematic reviews. Prescriptions of what is to be included miss the nuances and do not adequately account for study quality (or in this case even relevance to the question under review).

No other authors responded to our request for feedback.

Footnotes

- This definition comes from a taxonomy developed by Münscher et al. (2016, .htm). [↩]

- The original authors randomly assigned time slots, not individuals, to one of the foodservice conditions. There were very few timeslots (e.g., two time slots at three different schools in Denmark), and one cannot confidently expect the differences between, say, students who eat in an earlier time slot vs. those who eat in a later time slot, to even out over such a small number of time slots (e.g., maybe 2 out of 3 earlier time slots were assigned to the dish-of-the-day condition, and those who attend earlier time slots are less likely to prefer veggie balls). In addition, there is a problem of non-independence of observations within each time slot; students may be more likely to choose veggie balls if another student in their time slot chooses veggie balls. In general, we do not believe any causal inferences from this study are justified. [↩]

- When you pool across countries (N = 362) – and there may be good reasons not to do this (e.g., if the intervention or setting was meaningfully different in the four countries) – the effect is directionally positive: 15.5% choosing the vegetarian option in the intervention condition vs. 12.7% in the control condition. [↩]

- It is worth noting that the original authors published this result despite finding no effect of the dish-of-the-day intervention. Publishing null results like this is not typical. [↩]

- The original authors did not directly report the results for the subsample of minority students. The meta-analysts told us that they contacted the original authors to try to get these results and did not receive a reply. [↩]

- By “signaling that this section [of the menu] is not for the non-vegetarians” (p. 192). [↩]

- For example, imagine you have a control condition in which it is easy to engage in a behavior and then an experimental condition in which it is harder to engage in the behavior. If making things harder reduces the behavior, that should probably be coded as a positive effect rather than as a negative effect. [↩]

- In the Vegetarian Menu condition, both vegetarian options are listed last, whereas in the Control Menu one of the vegetarian options is listed first. Thus, this finding may reflect an effect of presentation order rather than an effect of signaling. We learned from the second author that in a subsequent pre-registered study (.htm), published after the meta-analysts collected their data, they eliminated this confound (by counterbalancing order) obtainig a significant effect in the same direction. [↩]

- Another example from a JAMA paper not in the meta-analysis (.htm): defaults have large effects on doctors prescribing generic drugs. [↩]

- This part of our conclusion aligns with a statement in the commentary from Szaszi et al: “instead of focusing on average effects, we need to understand when and where some nudges have huge positive effects and why others are not able to repeat those successes.” [↩]

- We did not cherry pick these studies. It takes a *long* time to do this, and we don’t have lots of time. We also didn’t want to make this post longer than it is. We invite interested readers to conduct their own audit(s) of this or other meta-analyses. At least in cases where the meta-analyst is averaging across very different kinds of studies, we’d be very surprised if you don’t uncover the same problems that we document here. [↩]