In the seventh installment of Data Replicada, we report our attempt to replicate a recently published Journal of Consumer Research (JCR) article entitled, “Product Entitativity: How the Presence of Product Replicates Increases Perceived and Actual Product Efficacy” (.html).

In this paper, the authors propose that “presenting multiple product replicates as a group (vs. presenting a single item) increases product efficacy perceptions because it leads consumers to perceive products as more homogenous and unified around a shared goal” (abstract).

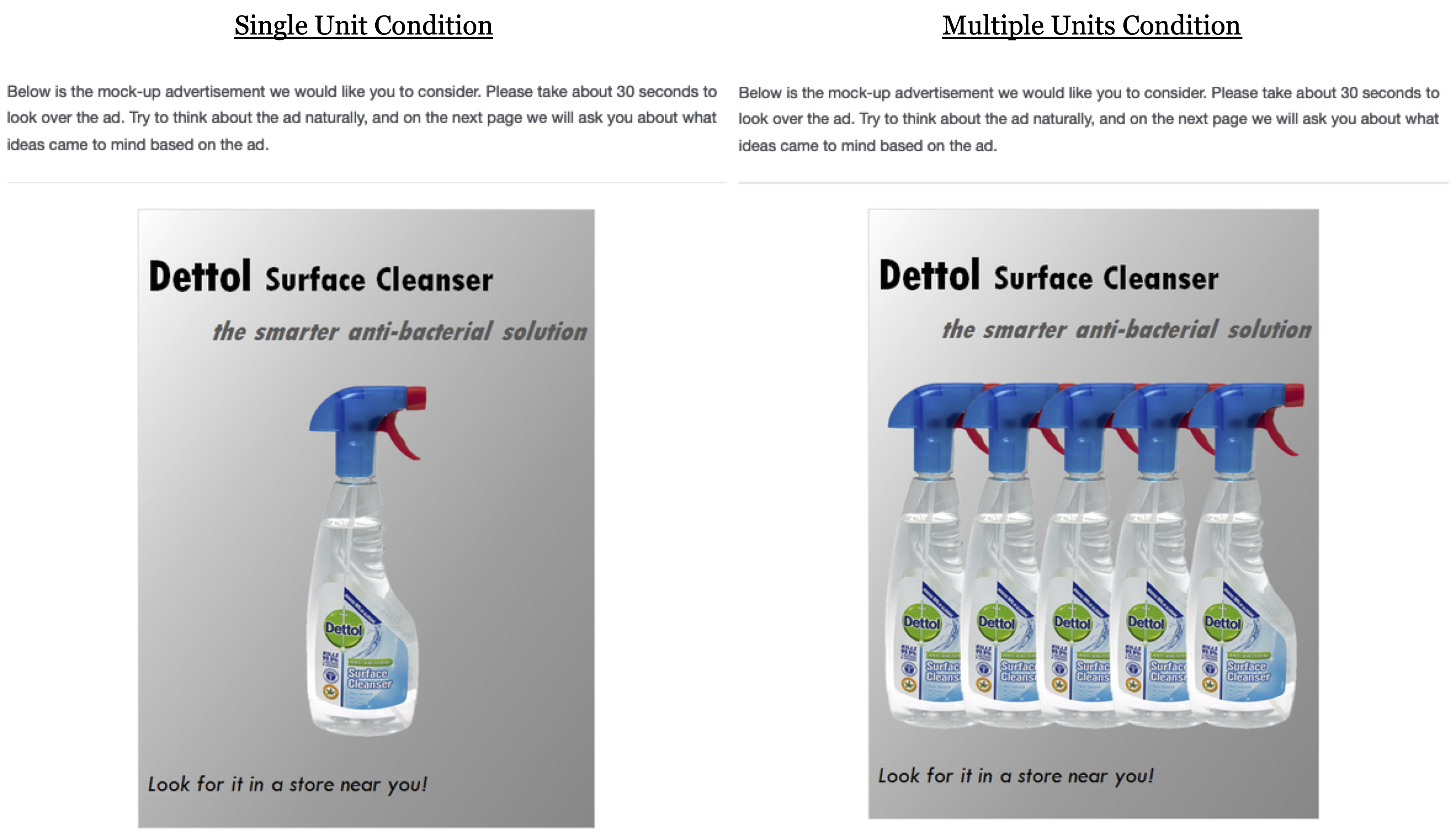

This JCR paper contains five studies. We chose to replicate Study 1 (N = 87) because it was the only study run on MTurk. In this study, participants saw an advertisement for a surface cleanser named Dettol. In the single-item condition, the advertisement displayed one bottle of Dettol. In the multiple-item condition, the advertisement displayed five bottles of Dettol (see below for stimuli). After seeing the advertisement, participants rated Dettol’s effectiveness. The authors found that participants who saw the ad displaying five bottles of Dettol judged it to be more effective than those who saw the ad displaying one bottle of Dettol.

We contacted the authors to request the materials needed to conduct a replication. They were extremely forthcoming, thorough, and polite. They shared the original Qualtrics file that they used to conduct that study, and we used it to conduct our replication. They also quickly answered a few follow-up questions that we had. We are very grateful to them for their help and professionalism.

The Replications

We ran three identical replications. The first two were run on MTurk using the same criteria the original authors used. The third was run on MTurk using a new feature that screens for only high-quality participants [1].

In the preregistered replications (https://aspredicted.org/gi726.pdf; https://aspredicted.org/pw4tv.pdf; https://aspredicted.org/n5tu8.pdf) we used the same survey as in the original study, and therefore the same instructions, procedures, images, and questions. These studies did not deviate from the original study in any discernible way, except that our consent form was necessarily different, our exclusion rules were slightly different [2], and we had at least 6.5 times the original sample size [3]. You can access our Qualtrics surveys here (.qsf1; .qsf2; .qsf3), our materials here (.pdf); our data here (.csv1; .csv2; .csv3), our codebook here (.xlsx), and our R code here (.R).

In each study, participants saw one of two advertisements for Dettol:

After viewing the ad, participants then proceeded to a separate page on which they answered four questions that measured how effective they believed Dettol to be. Those questions were:

- In general, how effective do you think the Dettol you considered would be?

- How much do you think Dettol would help you clean your home?

- How effective do you think Dettol is in cleaning dirt and bacteria?

- How potent do you think the active ingredients in Dettol are?

Participants gave their answers on 9-point scales and we averaged them to create an index of perceived effectiveness [4].

Results

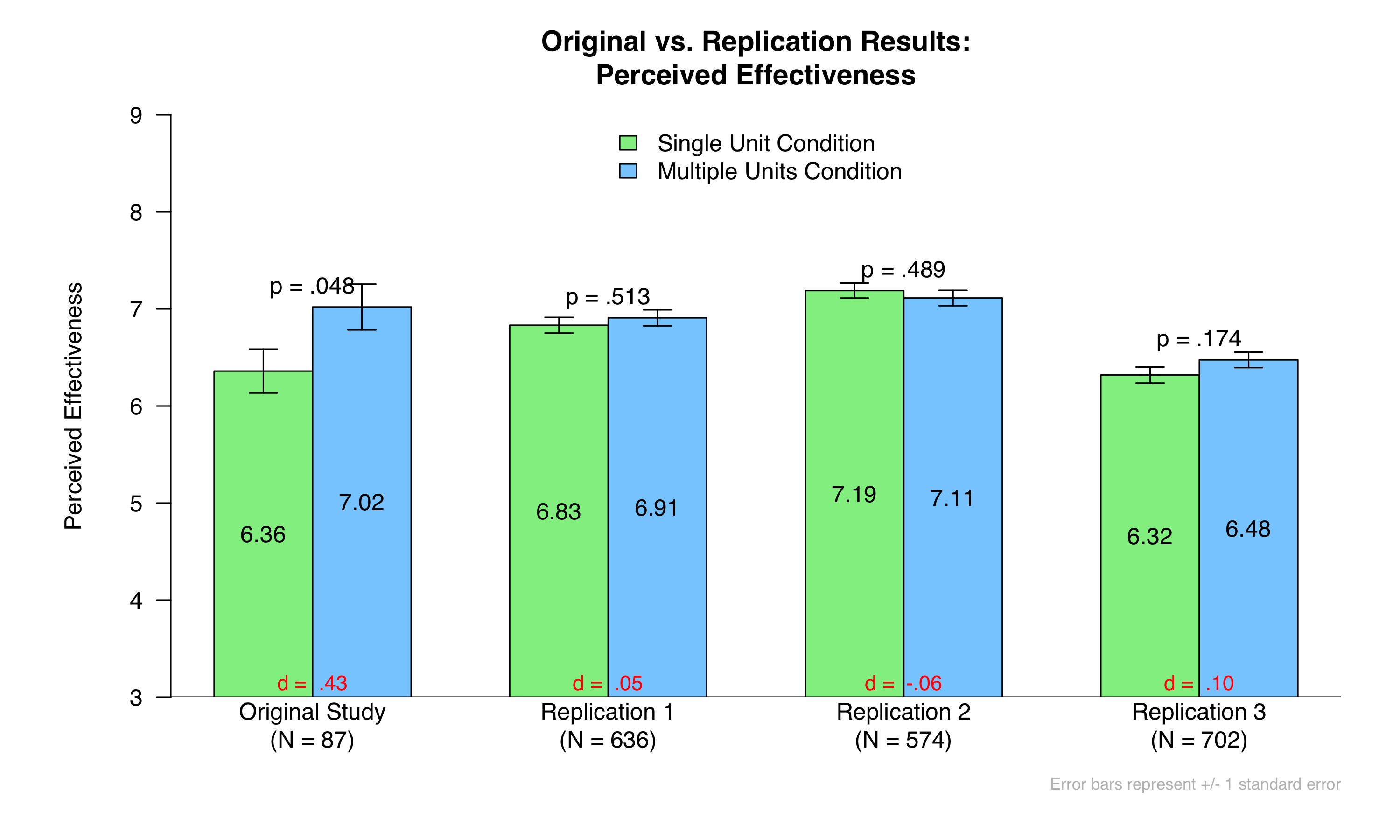

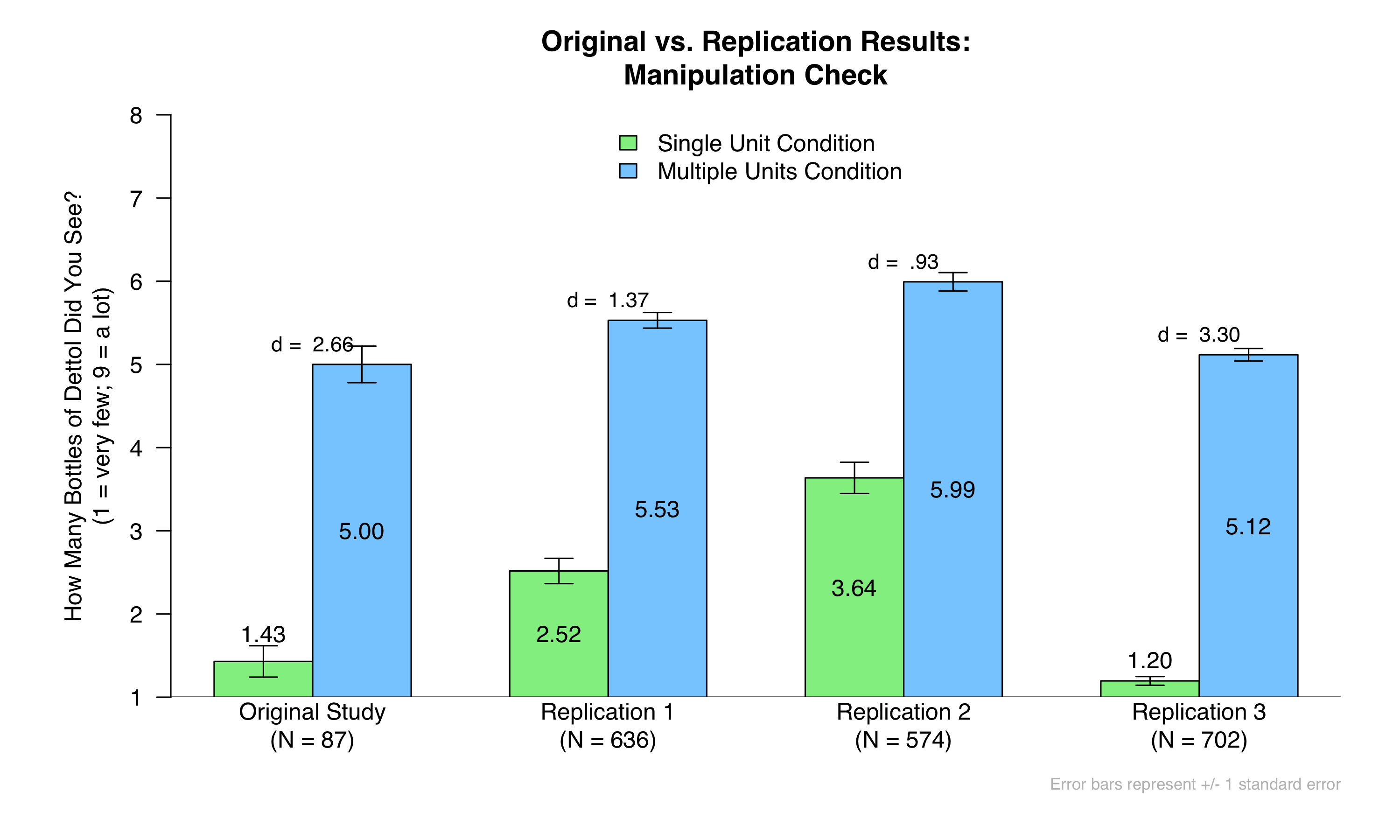

Here are the original vs. replication results:

As you can see, the original finding did not replicate. Participants did not judge Dettol to be significantly more effective after seeing an add that displayed five (vs. one) bottles of it.

As you can see, the original finding did not replicate. Participants did not judge Dettol to be significantly more effective after seeing an add that displayed five (vs. one) bottles of it.

If we want to be maximally optimistic, we can highlight that the most supportive evidence came from Replication 3, the sample that should include only the ostensibly high-quality “CloudResearch Approved Participants”. But even here, the result was not significant, and the effect size (d = .10) is much smaller than in the original (d = .43). If we take that d = .10 to be an estimate of the true effect, then to have 80% power we would need more than 2,900 participants [5]. The original study had 87. Thus, the best case scenario is that the effect is real but that the original study could not have detected it.

Detour: Are “CloudResearch Approved Participants” More Attentive?

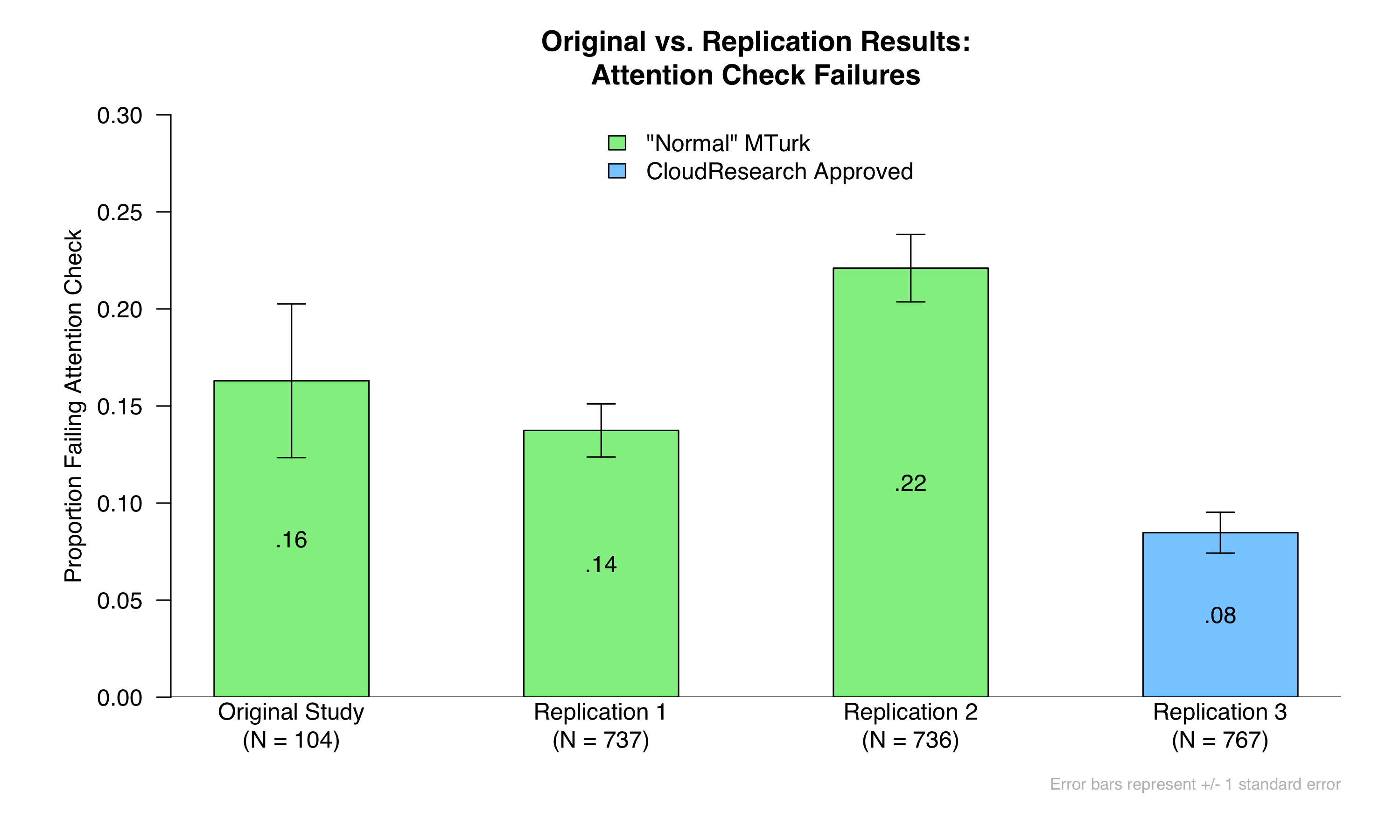

There has been some discussion about MTurk research quality declining since the pandemic (or perhaps even prior to that). One potential protection from that ostensible decline is to run studies on MTurk using only “CloudResearch Approved Participants” (.html). As mentioned, we did this in Replication 3. As shown below, it certainly looks like this population pays closer attention.

We will focus on two measures collected in the survey. One is an attention check. Near the end of the survey, participants were asked, “How often do you do the household shopping? Actually, to show us you’re paying attention, please click the number two below.” Here is the proportion of participants who failed this check across the original study and the three replications:

You can see that it does seem to work: Fewer participants failed the attention check in Replication 3 than in the other studies.

You can see that it does seem to work: Fewer participants failed the attention check in Replication 3 than in the other studies.

The second measure is a basic manipulation check. Participants were asked, “How many bottles of Dettol did you see in the ad?”, which they answered on a scale ranging from 1 = “Very few” and 9 = “A lot”. Here are the results of that manipulation check across the four studies:

In all studies, the condition differences in the manipulation check were large and very significant (ps < .001). But the effect was the largest in Replication 3 (d = 3.30), when we used CloudResearch Approved Participants.

In all studies, the condition differences in the manipulation check were large and very significant (ps < .001). But the effect was the largest in Replication 3 (d = 3.30), when we used CloudResearch Approved Participants.

From all of this we can tentatively conclude that using CloudResearch Approved Participants results in a sample that is more attentive than both modern-day and older MTurk samples. With that said, it is worth noting that “more attentive” does not necessarily mean “better.” For example, it is possible that CloudResearch Approved Participants are more likely to be professional survey takers, and thus less naïve and/or less representative. Going forward, whenever possible, we will continue to run replications (and our own research studies) using both sample types, so as to continue to learn about any differences that might emerge.

Conclusion

In sum, using at least 6.5 times the sample size as the original study, we do not find significant evidence that people judge products to be more effective when they see many versus one replicate of that product. Although it is possible that a true and small effect may exist, a researcher would need a sample of thousands to reliably find out.

Author feedback

We appreciate the Data Colada team’s interest in our research. While we are ultimately disappointed that they did not replicate our findings, we do see value in their work and would like to offer some thoughts regarding the replication attempt.

First, we appreciate the timeliness of this replication, in that it allowed the Data Colada team to compare “normal” MTurk samples to “CloudResearch Approved Participants.” It’s obvious to all of us that the population of MTurk workers has evolved over the years, especially since the start of the pandemic, and researchers are faced with a difficult situation where the participants they once relied on are now of questionable reliability. We also agree that “more attentive” does not necessarily mean “better,” and that participant naiveté (or lack thereof) in online samples may be an even more challenging hurdle than attentiveness. This replication was useful in providing an initial demonstration of some of the differences between samples, and we look forward to learning more about the extent of these differences.

We were happy to see that the Data Colada team found directional support in their third round of data collection, using the CloudResearch Approved Participants. It is especially noteworthy that this was found in a study featuring an all-purpose cleaner that was run during a global pandemic characterized by supply chain shortages of cleaning products. That is, compared to when the original study was run in 2016, the current pandemic might have changed the weight of different evaluative criteria in determining participants’ perceptions of a cleaner’s value and efficacy. For example, while opinions about household cleaners might not ordinarily be very strong, we think it’s plausible that, under a global pandemic, opinions about household cleaners may be more strongly held, more directly related to specific product attributes (e.g., trusted brand names; familiar active ingredients or those that better fight coronavirus), and overall more resistant to change. Combined with the data quality issues already discussed, the general challenges of conducting online research at this time (e.g., see recent working papers: Arechar and Rand 2020; Rosenfeld et al. 2020), and the fact that effect sizes can differ by context, it may be possible that the “true” effect size of displayed quantity is larger than what the replications indicate. Ultimately, we believe our paper demonstrates a true (if not particularly large) effect, and we hope that readers will look to the additional studies in our published paper to learn more about the effects of presenting multiple units (vs. a single unit) of a product.

Again, we thank the Data Colada team for their interest in our work.

Footnotes.

- Specifically, in the first two replications, we used MTurkers with a >90% approval rating. In the third replication, we used only “CloudResearch Approved Participants” with a >90% approval rating. We actually intended to run only two replications, one with the original authors’ criteria and the second with CloudResearch Approved Participants. But because of an error, the second replication also used “normal” MTurk participants. [↩]

- For quality control, we pre-registered to exclude all observations associated with duplicate MTurk IDs or IP Addresses, and to exclude those whose actual MTurk IDs were different than their reported IDs (though we were unable to do this in the first replication, because a typo prevented us from recording participants’ actual MTurk IDs). On the advice of the original authors, we advertised that this survey could not be taken on a smartphone or any screen of smartphone size, and we excluded those who did so (based on their metadata). Finally, because of an oversight, we neglected to pre-register to exclude participants who failed an attention check that came later in the survey, even though the original authors did exclude these participants. We think it makes sense to stay true to the original, and so this post reports the results with those participants excluded (though the results are nearly identical either way: see .pdf and associated .R code). To see the breakdown of all of our exclusions, click here: .pdf. [↩]

- We chose such a large sample because, after exclusions, we like to have at least 300 per cell for replications. Anything less than that provides an effect size estimate that is a bit too noisy for our taste. This is obviously an arbitrary cutoff. [↩]

- After answering these questions, participants went on to complete 37 additional ratings on subsequent screens. Some of these questions asked about participants’ thoughts during the ad (e.g., “How much did you think about the potency of Dettol’s active ingredients?”), about the extent to which Dettol’s products seem like a coherent group (e.g., “To what extent do you think Dettol’s products seem like individual and separate units versus a tight, unified group of products?”), about participants’ purchase likelihood and liking of Dettol (e.g., “How likely would you be to consider purchasing Dettol if you saw it in a store?”), and about how available and popular Dettol is (e.g., “Based on the ad, how widely available do you think Dettol is?”). As of this writing, we have not systematically analyzed these measures. [↩]

- If you want 95% power, you’d need close to 5,000 participants. [↩]