This is the last post in a four-part series detailing evidence of fraud in four academic papers co-authored by Harvard Business School Professor Francesca Gino. It is worth reiterating two things. First, to the best of our knowledge, none of Gino’s co-authors carried out or assisted with the data collection for the studies in this series. Second, in this effort we collaborated with a team of early career researchers who have chosen to remain anonymous.

Part 4: Forgetting The Words

Gino, Kouchaki, & Casciaro (2020), Study 3a

"Why Connect? Moral Consequences of Networking with a Promotion or Prevention Focus"

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

In this paper (.htm), the authors propose that being in a particular mindset affects how people feel about networking. The mindsets they investigated are known as "promotion focus" and "prevention focus". Promotion focus involves thinking about what one wants to do, while prevention focus involves thinking about what one should do [1]. The authors predicted that people would feel worse about networking when in a "prevention focused" mindset.

Perhaps an easy way to remember the prediction: promotion-focus makes you more OK with self-promotion.

Here we focus on Study 3a. This study has a lot going on, and we will describe only what's relevant for spotting the fraud.

MTurk participants (N = 599) were asked to do a short writing task to induce a promotion mindset, a prevention mindset, or no mindset at all. They were randomly assigned to write about one of three things:

- A hope or aspiration (Promotion condition)

- A duty or obligation (Prevention condition)

- Their usual evening activities (Control condition)

After the writing task, participants imagined being at a social (networking) event in which they made some professional connections. (See full materials (.docx), or just the scenario (.txt)).

Participants then rated, on 7-point scales, “the extent to which the situation you read about made you feel”: dirty, tainted, inauthentic, ashamed, wrong, unnatural, impure. The average of these seven items represents the key dependent variable in this post, and we will refer to it as “moral impurity”. Keep in mind that on these scales a 1 means that they saw nothing wrong with networking and a 7 means that they found networking to be maximally impure.

Finally, and critically for our purposes, participants were asked to list 5-6 words describing their feelings about the networking event. The researchers didn’t really care about these words. They did not even analyze them. But we will care a lot. And we will analyze them. A lot.

Results

Average scores on the 7-item moral impurity measure differed significantly across conditions, F(2, 596) = 17.69, p < .0000001. As predicted, participants felt more impure about the networking event in the Prevention condition than in the Promotion condition.

The Dataset

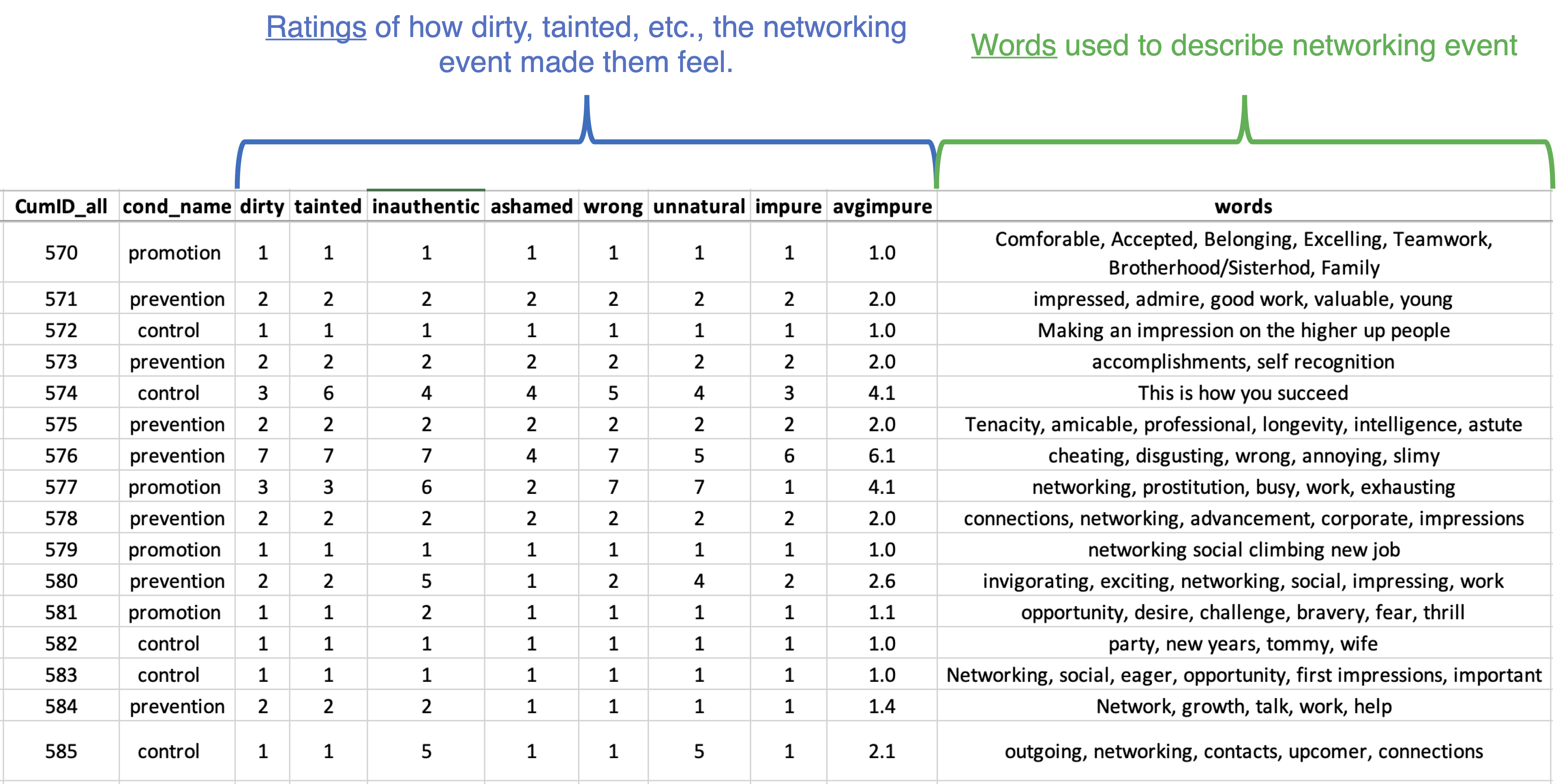

Let's first orient ourselves to the dataset, which was posted on the OSF in 2020 (.htm) [2].

The top row shows a participant who provided a ‘1’ to all the impurity items. This participant didn’t feel at all dirty, tainted, inauthentic, etc., by being at the networking event. The words they wrote were positive as well: Comfortable, Accepted, Belonging, etc.

Positive ratings, positive words. Makes sense.

The Moral Impurity Ratings

This plot shows the average moral impurity rating for every participant in the study.

In the Control condition (on the left), we see that 92 participants gave 1.0s; they indicated feeling not at all impure on any of the scale items. We don't know how many 1.0s to expect, but it seems reasonable that many participants would answer in this way. There is arguably nothing intrinsically dirty or inauthentic about befriending co-workers.

But now take a look at the Prevention condition (in the middle). In this condition, which the authors predicted to elicit higher (more impure) ratings, there were way fewer 1.0s. Instead, there were many 2.0s and 3.0s.

This seems strange. These are averages of seven ratings. The simplest and most common 2.0 is obtained when all seven ratings are 2s. While it does not (to us) seem surprising for many people to answer 1 to every item on the scale, it does seem surprising (to us) for so many people to answer 2 or 3 to every item on the scale, to feel a little bit dirty, and a little bit inauthentic, and a little bit ashamed, etc. Indeed, there were very few 2.0s and 3.0s in the other two conditions.

This led us to suspect that the data in the Prevention condition were tampered with, that some of the “all 1s” were replaced by “all 2s” and “all 3s”. This would be extremely easy for a data tamperer to do.

We also noticed that the Promotion condition has no very high values and a whole lot of 1.0s. That led us to suspect that perhaps some of the higher values were manually changed to 1.0s.

This annotated version of the previous figure summarizes our suspicions.

Now we are going to put those suspicions to the test. Using the words.

The Researchers Didn’t Care About The Words. But We Do.

Critically, the authors were not really interested in the words that participants generated; the words task was there merely to help participants remember the networking event before doing something else. And so, to our knowledge, those words were never analyzed. They are not mentioned in the study’s Results section.

This is important because someone who wants to fabricate a result may change the ratings while forgetting to change the words.

And it seems that that's what happened. In our analyses we will contrast ratings of the networking event, which were tampered with, with words describing the networking event, which, it seems, were not [3].

In order to perform analyses on the words, we needed to quantify what they express. To do this, we had three online workers, blind to condition and hypothesis, independently rate the overall positivity/negativity of each participant’s word combination, on a scale ranging from 1 = extremely negative to 7 = extremely positive. We averaged those ratings to create, for each participant, a measure of how positive or negative their words were [4].

Examining Fraud #1: Suspicious 2.0s and 3.0s in the Prevention Condition

Our first (and strongest) suspicion was that the (morally impure) 2.0s and 3.0s in the Prevention condition used to be 1.0s (so, not at all impure). If that is true, and if their words were not altered, then we should see that the words associated with those 2.0s and 3.0s are too positive.

To see if that’s the case, let’s first just look directly at the raw data.

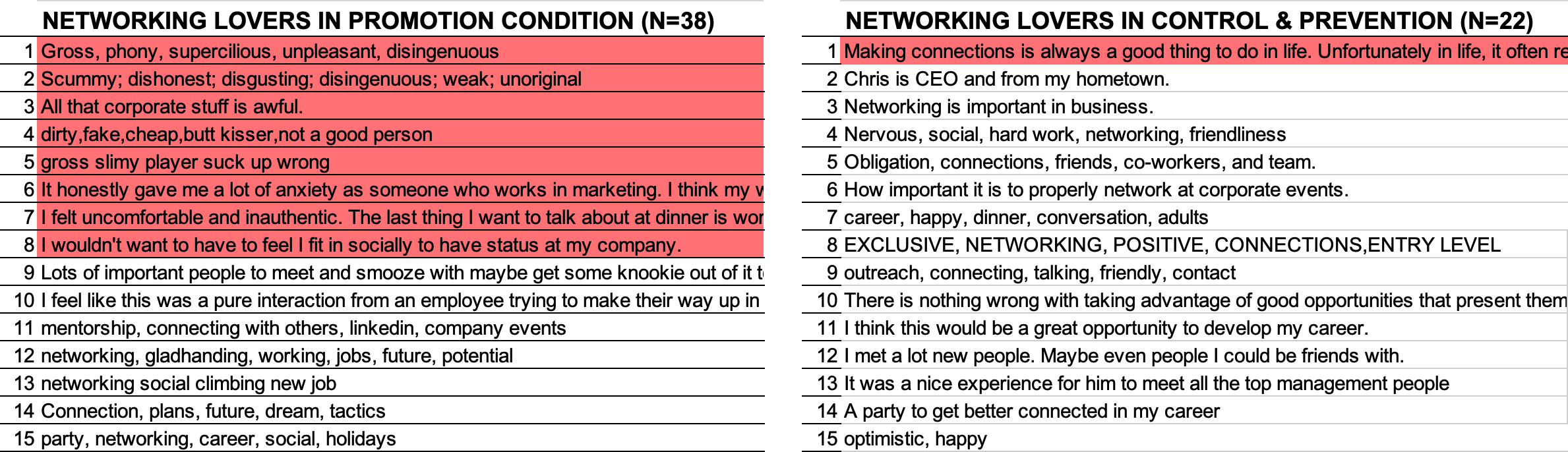

The screenshot below shows the words used by two groups of participants within the Prevention condition. On the left, we see the words written by the 18 participants with ratings of 3.0. We suspected that many of these 3.0s actually gave ratings of 1.0, and thus were actually not at all bothered by networking. On the right, we see the words written by the 22 participants with average ratings between 2 and 3, whose ratings we believed to be legitimate, and thus who were truly bothered by networking.

The rows below are sorted by how positive the words are, so that the most negative word combinations are at the top. We've highlighted (in blue) those rated positively (above the scale midpoint).

Since 3.0 represents a more impure rating than values between 2 and 3, we should see that the 3.0s wrote more negative things. But instead they wrote (much) more positive things. This doesn’t make sense. Unless, of course, some of those 3.0s used to be 1.0s.

We can go beyond this visual inspection of the 3.0s to perform a quantitative analysis of the whole dataset.

First, using every observation except for those suspicious Prevention-condition 'all 2s' and 'all 3s', we estimate the association between the impurity rating, and the negativity of the words. We then see whether those suspicious 2.0s and 3.0s are associated with words that are much too positive. And they are.

The plot below shows the results. The blue line depicts the (non-linear) relationship between the average moral impurity rating and how positive the words are [5]. Higher impurity ratings are associated with less positive words. Good.

The four blue points on/near the line represent the average word rating for participants who provided moral impurity ratings of 1.0, between 1.0 and 2.0, between 2.0 and 3.0, and greater than 3.0. They all make sense.

But check out those red points, which indicate the average word rating associated with the ‘all 2s’ and ‘all 3s’ in the Prevention condition. They don’t make sense, as they are associated with words that are way too positive. Indeed, they are as positive as the 'all 1s' in the rest of the dataset. This is additional evidence that these ‘all 2s’ and ‘all 3s’ used to be ‘all 1s’.

Examining Fraud #2: Suspicious 1.0s in the Promotion Condition

Our second (and weaker) suspicion was that some ratings of high moral impurity in the Promotion condition were changed to 1.0s.

To test this, we rely on a subset of participants we refer to as “Networking Lovers.” These are participants who gave a ‘1’ to all seven moral impurity items (and so found nothing impure about networking), and who also gave a ‘7’ to four subsequent items that assessed how much they are likely to voluntarily engage in networking behaviors in the next month (and so were maximally interested in future networking) [6].

These Networking Lovers were maximally positive about networking on every rating scale available to them. And so we would expect them to have written positive things about the networking event. But, if some of those 1.0s had been tampered with and had actually rated networking as morally impure, then some of these Networking Lovers should have used fairly negative words to describe networking. And some did.

There were 38 Networking Lovers in the Promotion condition, and 22 combined in the Control and Prevention conditions. In the figure below, we show you the 15 Networking Lovers in each of these two groups who wrote the most negative words. We’ve highlighted every word combination that was rated negatively (below the scale midpoint).

If some of the 1.0s in the Promotion condition were tampered with, edited by hand from higher (more impure) values, then in that condition we should expect to find some Networking Lovers who wrote words implying that they disliked networking. And we do. For example, one of these supposed Networking Lovers wrote "Gross, phony, supercilious, unpleasant, disingenuous". That's not what a real Networking Lover would say.

Overall, in the observations we don't think are fake (the Control and Prevention conditions), only one (out of 22) Networking Lovers wrote negative things about networking, and what that one person wrote was only mildly negative (rated a 3.3 out of 7). However, in the set of observations that we think include some fake data (the Promotion condition), 8 (out of 38) wrote negative things about networking, and in many cases what they wrote was very negative. On the one hand, this is a small sample, and we would never draw firm conclusions from this analysis alone. On the other hand, there should be extremely few Networking Lovers writing negative things about networking, let alone 8 in a single condition.

We take this as (tentative) evidence that some of those Promotion condition 1.0s used to have higher ratings of moral impurity.

What If We Just Analyze The Words?

If what we are saying is true – that a researcher faked the ratings but not the words – then the authors’ effect should go away when you just analyze the words [7]. And it does go away.

But it not only goes away; it for some reason reverses. People used more positive words to describe the networking event in the Prevention condition (M = 5.14, SD = 1.67) than in the Promotion condition (M = 4.74, SD = 1.92), suggesting that a promotion focus is bad for self-promotion [8]

We don’t yet know why. It could be random chance, as this p-value is not exactly awe-inspiring. It could be that the data were fabricated in more than just the way we’ve discussed here, and that this is some kind of unintended consequence of that. Or it could be that in fact the opposite of the authors’ hypothesis is actually true. Whatever the reason, it represents additional evidence that the data are fake [9].

We have received confirmation, from outside of Harvard, that Harvard's investigators did look at the original Qualtrics data file and that the data had been modified.

![]()

Code, data, and materials for all four posts in the series are (neatly organized) on ResearchBox.

https://researchbox.org/1630

For the next few days, you may need a code to access the box. That code is: RFLRKH

Author feedback.

Our policy is to solicit feedback from authors whose work discuss. We did not do so this time, given (1) the nature of the post, (2) that the claims made here were presumably vetted by Harvard University, (3) that the articles we cast doubt on have already had retraction requests issued, and (4) that discussions of these issues were already surfacing on social media and by some science journalists, without their having these facts, making a traditional multi-week back-and-forth with authors self-defeating.

Footnotes.

- This is a simplified summary of promotion- vs prevention-focus. For an accessible overview, check out this Harvard Business Review article: .htm [↩]

- We’ve renamed some variables and re-ordered some columns to make this easier to digest. [↩]

- Or at least were less likely to be. To be clear, as in the previous cases in this series, we may have uncovered only a subset of the tampered observations. Moreover, these data may have been tampered with in multiple ways, including simply switching condition labels, which would not produce a mismatch between words and ratings. Only those with access to the original Qualtrics data files would know for sure. [↩]

- The use of these raters is new for this post. For the 2021 HBS report we relied instead on sentiment analysis, performed with the “Vader” package in R. But when we were re-analyzing the data for this post, we noticed that the sentiment algorithm is not always great at capturing sentiment with so few words. For example, it gave a (slightly) net *positive* rating to the word combination: “Wow, liar, false, delusional, braggart.” The sentiment scores we used previously and the average of the human ratings we are now using correlate at r = .81. The correlations among raters ranged from r = .87 to r = .89. Our results/conclusions do not at all depend on which metric we use. [↩]

- We drew this line using a GAM, including only those observations that we believed to be less likely to be fake (i.e., those that were not all 2s and all 3s in the Prevention condition). [↩]

- For example, one question was “To what degree will you try to strategically work on your professional network in the next month?” All four items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 = not at all to 7 = very much. [↩]

- This presumes that the authors’ hypothesis was not supported in the data before it was fake. We think it’s unlikely that someone would fake data if the finding is already there. [↩]

- The words were most negative in the Control condition (M = 4.60, SD = 1.93). This difference is statistically significant: p = .026 ((And it is p = .031 if you use sentiment analysis to rate the words. [↩]

- One piece of additional evidence. Our hypotheses about how the data are fake suggests that many more observations were altered in the Prevention condition (i.e., all those 2.0s and 3.0s) than in the other two conditions (i.e., just a few Promotion condition observations). If this is true and, again, if the words were not altered, then the correlation between the moral impurity ratings and the word ratings should be weaker in the Prevention condition. And, indeed, that correlation is -.56 in the Control condition, -.49 in the Promotion condition, but only -.20 in the Prevention condition. [↩]