The fortuitous discovery of new fake data.

For a project I worked on this past May, I needed data for variables as different from each other as possible. From the data-posting journal Judgment and Decision Making I downloaded data for ten, including one from a now retracted paper involving the estimation of coin sizes. I created a chart and inserted it into a paper that I sent to several colleagues, and into slides presented at an APS talk.

An anonymous colleague, “Larry,” saw the chart and, for not-entirely obvious reasons, became interested in the coin-size study. After downloading the publicly available data he noticed something odd (something I had not noticed): while each participant had evaluated four coins, the data contained only one column of estimates. The average? No, for all entries were integers; averages of four numbers are rarely integers. Something was off.

Interest piqued, he did more analyses leading to more anomalies. He shared them with the editor, who contacted the author. The author provided explanations. These were nearly as implausible as they were incapable of accounting for the anomalies. The retraction ensued.

Some of the anomalies

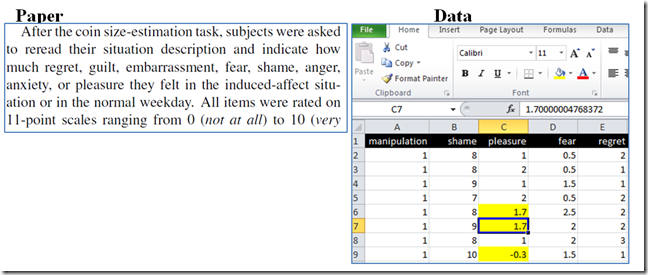

1. Contradiction with paper

Paper describes 0-10 integer scale, dataset has decimals and negative numbers.

2. Implausible correlations among emotion measures

Shame and embarrassment are intimately related emotions, and yet they are correlated negatively in the data r = -.27. Fear and anxiety: r = -.01. Real emotion ratings don’t exhibit these correlations.

3. Impossibly similar results

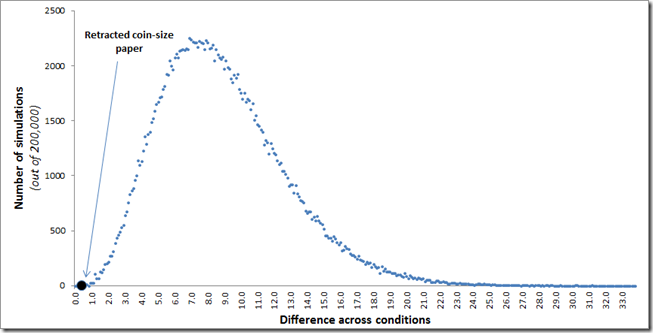

Fabricated data often exhibit a pattern of excessive similarity (e.g., very similar means across conditions). This pattern led to uncovering Sanna and Smeesters as fabricateurs (see “Just Post It” paper). Diederik Stapel’s data also exhibit excessive similarity, going back to his dissertation at least.

The coin-size paper also has excessive similarity. For example, coin-size estimates supposedly obtained from 49 individuals across two different experiments are almost identical:

Experiment 1 (n=25): 2,3,3,3,3,4,4,4,4,4,5,5,5,5,5,5,5,6,6,6,6,6,6,6,7

Experiment 2 (n=24): 2,3,3,3,3,4,4,4,4,4,5,5,5,5,5,5,_,6,6,6,6,6,6,6,7

Simulations drawing random samples from the data themselves (bootstrapping) show that it is nearly impossible to obtain such similar results. The hypothesis that these data came from random samples is rejected, p<.000025 (see R code, detailed explanation).

Who vs. which

These data are fake beyond reasonable doubt. We don’t know, however, who faked them.

That question is of obvious importance to the authors of the paper and perhaps their home and granting institutions, but arguably not so much to the research community more broadly. We should care, instead, about which data are fake.

If other journals followed the lead of Judgment and Decision Making and required data posting (its editor Jon Baron, by the way, started the data posting policy well before I wrote my “Just Post It”), we would have a much easier time identifying invalid data. Some of the coin-size authors have a paper in JESP, one in Psychological Science, and another with similar results in Appetite. If the data behind those papers were available, we would not need to speculate as to their validity.

Author's response

When discussing the work of others, our policy here at Data Colada is to contact them before posting. We ask for feedback to avoid inaccuracies and misunderstandings, and give authors space for commenting within our original blog post. The corresponding author of the retracted article, Dr. Wen-Bin Chiou, wrote to me via email:

Although the data collection and data coding was done by my research assistant, I must be responsible for the issue.Unfortunately, the RA had left my lab last year and studied abroad. At this time, I cannot get the truth from him and find out what was really going wrong […] as to the decimal points and negative numbers, I recoded the data myself and sent the editor with the new dataset. I guess the problem does not exist in the new dataset. With regard to the impossible similar results, the RA sorted the coin-size estimate variable, producing the similar results. […] Finally, I would like to thank Dr. Simonsohn for including my clarifications in this post.

[See unedited version]

Uri's note: the similarity of data is based on the frequency of values across samples, not their order, so sorting does not explain that the data are incompatible with random sampling.