Recently Science published a paper concluding that people do not like sitting quietly by themselves (.html). The article received press coverage, that press coverage received blog coverage, which received twitter coverage, which received meaningful head-nodding coverage around my department. The bulk of that coverage (e.g., 1, 2, and 3) focused on the tenth study in the eleven-study article. In that study, lots of people preferred giving themselves electric shocks to being alone in a room (one guy shocked himself 190 times). I was more intrigued by the first nine studies, all of which were very similar to each other. [1]

Opposite inference

The reason I write this post is that upon analyzing the data for those studies, I arrived at an inference opposite the authors’. They write things like:

Participants typically did not enjoy spending 6 to 15 minutes in a room by themselves with nothing to do but think. (abstract)

It is surprisingly difficult to think in enjoyable ways even in the absence of competing external demands. (p.75, 2nd column)

The untutored mind does not like to be alone with itself (last phrase)

But the raw data point in the opposite direction: people reported to enjoy thinking.

Three measures

In the studies, people sit in a room for a while and then answer a few questions when they leave, including how enjoyable, how boring, and how entertaining the thinking period was, in 1-9 scales (anchored at 1 = “not at all”, 5 = “somewhat”, 9 = “extremely”). Across the nine studies, 663 people rated the experience of thinking, the overall mean for these three variables was M=4.94, SD=1.83, not significantly different from 5, the midpoint of the scale, t(662)=.9, p=.36. The 95% confidence interval for the mean is tight, 4.8 to 5.1. Which is to say, people endorse the midpoint of the scale composite: “somewhat boring, somewhat entertaining, and somewhat enjoyable.”

Five studies had means below the midpoint, four had means above it.

I see no empirical support for the core claim that “participants typically did not enjoy spending 6 to 15 minutes in a room by themselves.” [2]

Focusing on enjoyment

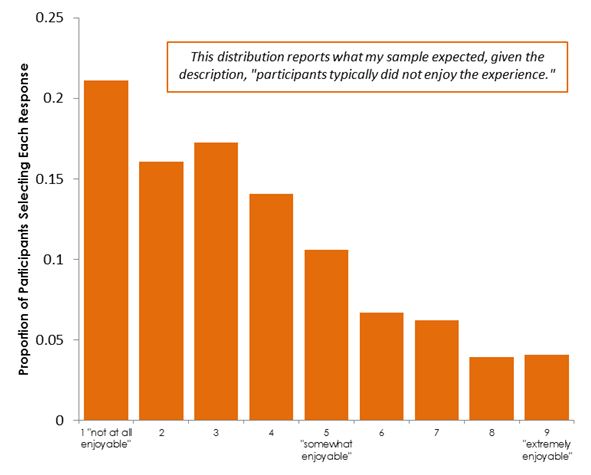

Because the paper’s inferences are about enjoyment I now focus on the question that directly measured enjoyment. It read “how much did you enjoy sitting in the room and thinking?” 1 = “not at all enjoyable” to 5 = “somewhat enjoyable” to 9 = “extremely enjoyable”. That’s it. OK, so what sort of pattern would you expect after reading “participants typically did not enjoy spending 6 to 15 minutes in a room by themselves with nothing to do but think.”?

Rather than entirely rely on your (or my) interpretations, I asked a group of people (N=50) to specifically estimate the distribution of responses that would lead to that claim. [3] Here is what they guessed:

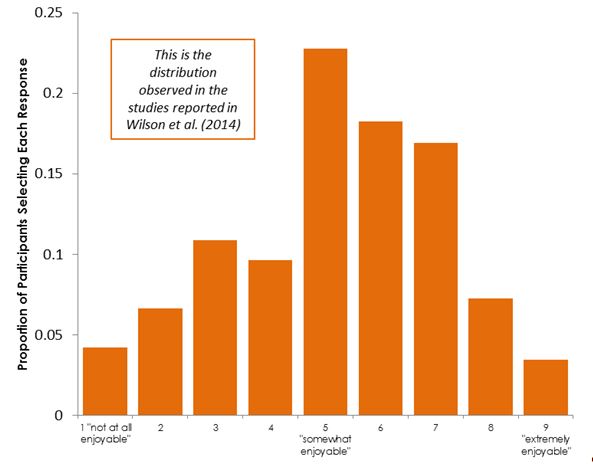

And now, with that in mind, let’s take a look at the distribution that the authors observed on that measure: [4]

Out of 663 participants, MOST (69.6%) said that the experience was somewhat enjoyable or better. [5]

If I were trying out a new manipulation and wanted to ensure that participants typically DID enjoy it, I would be satisfied with the distribution above. I would infer people typically enjoy being alone in a room with nothing to do but think.

It is still interesting

The thing is, though that inference is rather directly in opposition to the authors’, it is not any less interesting. In fact, it highlights value in manipulations they mostly gloss over. In those initial studies, the authors try a number of manipulations which compare the basic control condition to one in which people were directed to fantasize during the thinking period. Despite strong and forceful manipulations (e.g., Participants chose and wrote about the details of activities that would be fun to think about, and then were told to spend the thinking period considering either those activities, or if they wanted, something that was more pleasant or entertaining), there were never any significant differences. People in the control condition enjoyed the experience just as much as the fantasy conditions. [6] People already know how to enjoy their thoughts. Instructing them how to fantasize does not help. Finally, if readers think that the electric shock finding is interesting conditional on the (I think, erroneous) belief that it is not enjoyable to be alone in thought, then the finding is surely even more interesting if we instead take the data at face value: Some people choose to self-administer an electric shock despite enjoying sitting alone with their thoughts.

Authors' response

Our policy at DataColada is to give drafts of our post to authors whose work we cover before posting, asking for feedback and providing an opportunity to comment. Tim Wilson was very responsive in providing feedback and suggesting changes to previous drafts. Furthermore, he offered the response below.

We thank Professor Nelson for his interest in our work and for offering to post a response. Needless to say we disagree with Prof. Nelson’s characterization of our results, but because it took us a bit more than the allotted 150 words to explain why, we have posted our reply here.

![]()

- Excepting Study 8, for which I will consider only the control condition. Study 11 was a forecasting study. [↩]

- The condition from Study 8 where people were asked to engage in external activities rather than think is –obviously- not included in this overall average. [↩]

- I asked 50 mTurk workers to imagine that 100 people had tried a new experience and that their assessments were characterized as “participants typically did not enjoy the experience”. They then estimated, given that description, how many people responded with a 1, a 2, etc. Data. [↩]

- The authors made all of their data publicly available. That is entirely fantastic and has made this continuing discussion possible. [↩]

- The pattern is similar focusing in the subset of conditions with no other interventions. Out of 240 participants in the control conditions, 65% chose midpoint or above. [↩]

- OK, a caveat here to point out that the absence of statistical significance should not be interpreted as accepting the null. Nevertheless, with more than 600 participants, they really don’t find a hint of an effect, the confidence interval for the mean enjoyment is (4.8 to 5.1). Their fantasy manipulations might not be a true null, but they certainly are not producing a truly large effect. [↩]